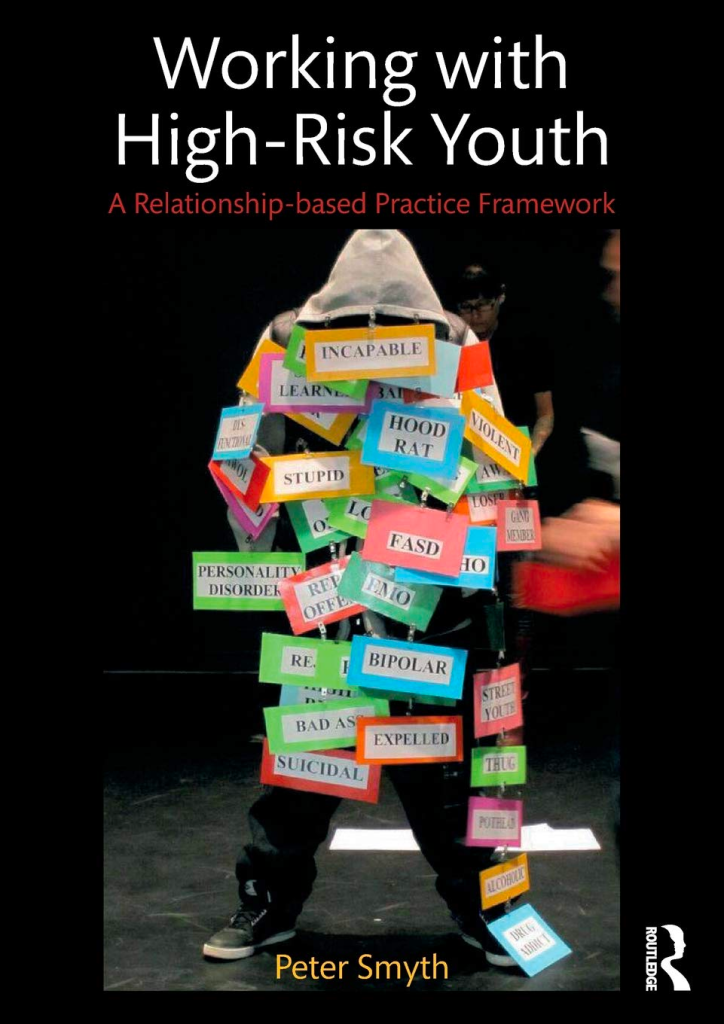

For a while, Working with High-Risk Youth: A Relationship-based Practice Framework by Peter Smyth has held a spot on my “Must Read List.” The book underscores the significance of nurturing relationships and cultivating a culture of resilience, innovation, and empowerment, particularly for students grappling with high-risk challenges such as mental health issues, abuse, or navigating the complexities of government agencies. Smyth delves into the emotions of hopefulness and loneliness that students may experience, emphasizing the pivotal role positive relationships play in reshaping mindset and behaviour. This insightful read advocates for strength-based teaching and empowering learners, prompting me to reflect on my role as a school administrator and consider promising practices for supporting “At-Risk” students through specialized programming options. The conversation sparked by the book highlighted the nuanced and intricate responsibility of guiding students through alternative programming / expectations, stressing the need to empower and mobilize learners to recognize their potential and strengths.

As outlined by the Ontario Ministry of Education “alternative expectations are developed to help students acquire knowledge and skills that are not represented in the Ontario curriculum. They either are not derived from a provincial curriculum policy document or are modified so extensively that the Ontario curriculum expectations no longer form the basis of the student’s educational program. Because they are not part of a subject or course outlined in the provincial curriculum documents, alternative expectations are considered to constitute alternative programs or alternative courses.”

A program I’m personally familiar with in my district is the Supervised Alternative Learning (SAL) program. As the board website highlights, “Supervised Alternative Learning (SAL) is an option under the Education Act that allows alternative programming for secondary students aged 14-18, who find they are not benefiting within the regular school system. It is the parent’s decision to apply to SAL, in consultation with the school social worker and administration, by completing the appropriate application process and creating a SAL Plan (SALP).”

The program serves students who may present with the following challenges:

- Chronic absences from school

- Disengaged from school

- Difficulties coping with the traditional structured classroom

- May benefit from a practical, short-term employment experience

- May benefit from different life experiences to help gain personal awareness and knowledge, develop skills for problem-solving, decision-making and goal setting

Reflecting on Smyth’s “Getting Connected” framework, the pathway to a program such a SAL requires graceful navigation by school staff as both the student and their parent(s)/guardian(s) must see the intrinsic value and hope that comes from such an opportunity to be supported. It must be understood that a alternate program like SAL does not equate failure by any means. Rather, it speaks to potential, resilience and the empowered mindset required to take courageous action in the pursuit of self-improvement, leaning into personal strengths and finding personal success. Furthermore, such a program promotes the positive relationships that supports well-being. As Symth notes, “secure attachments helps children regulate their emotions so feelings they experience are not overwhelming (Smyth, 74).”

I highly recommend Working with High-Risk Youth: A Relationship-based Practice Framework for its compelling exploration of fostering relationships and creating a culture of resiliency, innovation, and empowerment for students. This insightful read offers hope and emphasizes the significance of strength-based teaching and empowering learners.

You must be logged in to post a comment.